Southpaw 17: Our First Jock President

How Donald Trump's jocky attitude brought us to the brink of societal collapse.

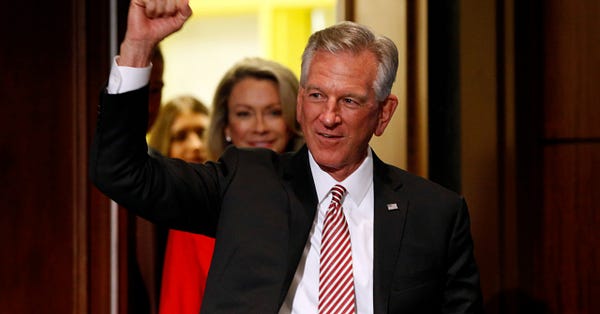

Dear Tommy Tuberville Hive,

Before we get to our main course this week, we’d like to update you on our favorite sitting senator from Alabama. On Thursday, Tommy really outdid himself:

This man is going to absolutely cruise to reelection in six years. At least he’ll keep providing us with good content along the way.

-Calder and Ian

The death rattles of the jock president were debilitatingly macho

On Monday, after spending nearly a week holed up in the White House in a deepening state of digital exile and political ridicule, Donald Trump finally re-emerged to seize the limelight. The purpose of his appearance was not to apologize for the deadly insurrection that he had fomented the week before, or even to defend himself against the charges that would shortly lead to his second impeachment. Rather, he took the stage to do what he does best: choreograph yet another bit of political theater. The script he chose for his post-insurrection encore was one that he has rehearsed many times before: “The Donald Presents: A Medal of Freedom!” And as he searched through his ever-thinning cast of ass-kissing cronies and half-hearted sycophants for someone to play beside him, he settled on one of his most reliable stock characters: the Jock, played on that night by none other than New England Patriots’ head coach Bill Belichick.

We’ve all seen this performance before. Since taking office in 2017, Trump has awarded 24 Medals of Freedom, 14 of which have gone to people who made their name in the sporting world. From a strictly athletic point of view, Trump’s honorees share basically nothing in common. The list includes athletes both dead and alive, including an Olympic wrestler, Babe Ruth, a plutocratic NASCAR owner, Tiger Woods, a couple of basketball stars that we’re too young to have heard of, and Mariano Rivera. From a political point of view, their only real unifying characteristic appears to be their membership in the exclusive club of Extremely Rich Macho Men, the same club which Trump has spent his entire personal and professional life trying unsuccessfully to join.

Of course, Trump did not choose to honor these men—they are all, with one exception, men—because he admires their athletic achievements or values their contributions to the mythology of American sports. They are selected, like everything else in Trumpworld, based on their ability to flatter his ego and pander to his image. Trump, who once lied about being a baseball star in high school, is perhaps the first true jock president, not because he is actually a successful or beloved athletic figure, but because he identifies more strongly than any past president with the essence of the jock ethos. He idolizes the traits that distinguish a thoroughbred jock from a run-of-the-mill sportsperson: the eagerness to do violence in the name of competition; the willingness to cheat and lie if it helps them win; the penchant for showboating and boasting and arrogance.

And yet Trump is not satisfied with the relatively benign delusion that he shares something essential and important with the Jock archetype. Instead, he has taken his own self-delusion to even more radical extremes, concluding that his affection for successful and rich athletes is in fact evidence of their affection for him. Trump has broadcast this belief before, most memorably during the Clemson Tigers’ post-championship visit to the White House in 2019, when he nixed the typical presidential pomp-and-circumstance to feed his guests a banquet befitting his own culinary preferences during a government shutdown. “I think we’re going to serve McDonald’s, Wendy’s, Burger King, with some pizza,” the president said at the time. “I would think that’s their favorite food. So we’ll see what happens.” What the whole stunt revealed was that Trump so completely identifies with the jock ethos that he is actually unable to distinguish between his own wants and desires and the wants and desires of the jocks whose approval he so desperately covets. “I would think that’s their favorite food”—meaning, of course, that his guests, like him, must also be fast-food guzzling, vaguely angry men who fancy themselves champions. The inescapable lesson of the evening, captured in one of the defining photos of the past four years, is that Trump is a coward who thinks he is a hero.

It was this particular delusion that set the stage for Trump’s latest and most humiliating flop. Admittedly, even outside the damaged logic of Trump’s worm-eaten brain, Bill Belichick seemed like a natural candidate for the role that Trump needed to fill. A legendary grump known for his autocratic leadership style and exaggeratedly adversarial relationship with the press, Belichick is in many ways an ur-Trumpian figure, a wannabe-despot who tapped into the aesthetic impulses and emotional undercurrents of Trumpism before Trump himself did. Unsurprisingly, the grizzled Patriots vet is also a long-time political ally of the president, having written a nauseatingly fawning letter to then-candidate Trump on the eve of the 2016 election. For the past decade, he has also been in the employ of Patriots owner Robert Kraft, a Trump mega-donor who gave nearly $1 million to Trump’s inaugural committee in 2016.

It therefore came as a legitimate shock when Belichick publicly declined Trump’s invitation. Whether Belichick was moved by genuine pangs of conscience or simply got spooked by the ensuing public relations nightmare is anyone’s guess. The statement that he issued to announce his decision made vague reference to his “great reverence for our nation’s values” and commitment to “conversations about social justice, equality, and human rights” without mentioning the obvious fact that his would-be host had just publicly undermined all of those values.

But perhaps the most surprising thing about the entire Belichick episode is that anyone is surprised at all. For the past four years, athletes have been doing exactly what Belichick did: declining to accept Trump’s invitations to the White House, citing, among other things, his obvious contempt for democracy, overt racism, undisguised disdain for the rule of law, gleeful vilification of immigrants, and unapologetic locker-room sexism. In typical fashion, the Right drew from its usual litany of coded insults to heap scorn and contempt on these athletes, while the Liberal Resistance gave them a subdued round of applause for their admirable but ultimately symbolic show of concern. Neither group actually listened to the substance of what they said or took their warnings seriously.

This is, in many ways, the story of the Trump presidency. As Osita Nwanevu argued this week in the New Republic, the Capitol insurrection may have marked a particularly ugly instance of Trump’s rhetoric inspiring real violence, but it was hardly the first. Nwanevu put it better than we ever could, so we’d like to include the first two paragraphs of his column here:

“Let’s get something straight. The press and many of our leaders have converged upon an implicit consensus that last Wednesday should be understood as the nadir of the Trump era—as a tipping point illustrating, for either the first or the most significant time, the deadly potential of his antics and rhetoric. They are wrong. In October 2018, a gunman animated by theories about migrant caravans that the president had promoted walked into a Pittsburgh synagogue and killed 11 people. Less than a year later, a gunman raging about an immigrant takeover of the country killed 23 in El Paso, Texas. The attack on the Capitol was a remarkable event—the violent denouement of an extraordinary attack on a presidential election. But those murders were, too, offensives against the democratic principle. In fact, they were made for precisely the same reasons. Stewing in a political climate the president shaped, and certain of a conspiracy to wrest American society from its rightful owners, these men took action. They killed.

And we moved on. The dampers and hydraulics of American political discourse absorbed the shock and kept us steadily on our path toward collapse. Tweets and tears, essays and columns, raised voices and mugging for cameras on cable television—each time, all of it preceded a forgetting so thorough, a refusal to deal seriously with the state of things so total, that we arrived at Wednesday’s events ready to have our eyes widened and our mouths set agape again, sputtering and stammering words we hoped would be of consequence.”

Trump has maintained control over the Republican party for many reasons, but one of the most powerful has been our collective insistence on forgetting the latest horror to make mental room for the next one. Nearly every day of the last four years has featured some sort of new Trump scandal. These scandals have dominated media coverage, but they ultimately added up to little besides further entrenchment.

And this brings us back to Bill Belichick’s Medal of Freedom. The point is not simply that Trump’s Medal of Freedom honorees have inspired shock and disgust before—remember, for instance, the minor uproar over Trump’s announcement during last year’s State of the Union address that he’d award the medal to Rush Limbaugh. Rather, the point is that professional athletes have in some ways been uniquely positioned to understand Trump’s admiration for violence and his lurid attraction to authoritarianism. This is, after all, the same man who routinely curried favor with his base by insulting Black athletes who spoke out against the murder of innocent Black people by agents of the state. The athletes who were the target of his pathetic fascistic rage—Kaepernick, but also innumerable WNBA players, LeBron James, Megan Rapinoe, Steph Curry, Doc Rivers—did not keep quiet about it. For four years, they said precisely what Belichick was too cowardly to say in his press release: that Trump is at heart a violent authoritarian motivated by avarice and hate and the lust for power. We heard them, nodded, and moved on.

Understood in this context, Belichick’s last-minute refusal takes on a whole new light. In the end, it was not simply a well-intentioned reversal or a small act of resistance. It was, in reality, an admission of guilt, an acknowledgment that, during four years of escalating violence and terror and brutality, Belichick had been backing the wrong team. Like so many others on both the right and the left, had had been deaf to the pleas and warnings of the players he claims to lead, and now he had become an unwilling pawn in a brutal game that he had helped to create.

Shortly after the election in 2016, reporters pressed Belichick at a press conference about the letter he had written on the eve of the election, asking him whether he had intended it as an implicit endorsement of Trump and his policies. Belichick skirted the question, claiming that he wasn’t “a political person” and denying that his comments had been “politically motivated.” When a reporter pushed him further, Belicheck cut him off, interjecting “Seattle”—the name of the Patriot’s opponent in the coming week—in the middle of a reporter’s question. When the reporter persisted, Belichick stonewalled him, repeating “Seattle, Seattle, Seattle,” until he broke off his line of questioning.

Four years later, Belichick found himself in a political snafu that he couldn’t stonewall his way out of. The equivocating, blustery statement that he issued to escape this situation may have been enough to get him out of immediate political hot water, but it will not be enough to drown out the word that will echo throughout every discussions of Belichick’s legacy from here on out: complicit. Complicit, complicit, complicit.

RODNEY’S ROUNDUP

Do you want to read about . . .

. . . how sports media has failed to hold the the NCAA to account? “Opinion: Alabama-Ohio State hoopla is a reminder that sports media has failed college athletes” by Alex Shultz in SF Gate (January 12, 2021).

. . . the equivocations of college coaches and what they’ll do in the wake of the Capitol riot? “College Coaches Will Have To Choose Where Their Loyalties Lie” by Maitreyi Anantharaman in Defector (January 14, 2021).

. . . a community coming together to help an aging man through COVID? “He Just Wanted to Play Catch. They Got Relief From Troubled Times.” by Mike Wilson in The New York Times (January 15, 2021).