Southpaw 25: How Did a 'Character Coach' Take Over The Houston Texans?

Dear loyal readers,

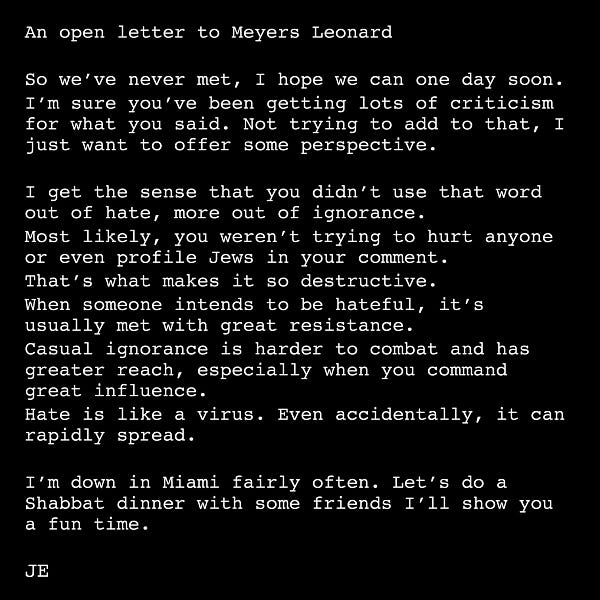

Racism in sports is sometimes more of a whisper than a shout. This week, however, it was a shout—and a very loud one, at that. On Monday, a video circulated on Twitter of Miami Heat center Meyers Leonard yelling an antisemitic slur on a livestream while playing Call of Duty, prompting the Heat to suspend him for a week. On Tuesday, Julian Edelman, the New England Patriots wide receiver, published the unusually level-headed statement on Twitter:

The warm feeling didn’t last too long. On Friday, a new video circulated of an announcer at a high school basketball game in Oklahoma calling the players on the Normal High School women’s team a racial slur for kneeling during the national anthem (in maybe a new low, the announcer blamed his low blood sugar for the outburst). We’ve written about the National Anthem Tantrum plenty of times before, but the video was a stark reminder of the racist vitriol that the conflict over the anthem inspires.

But this week, we’re moving into new territory: the Houston Texans’ Charlatan-in-Chief Jack Easterby. Happy reading!

-Calder & Ian

Jack Easterby has taken over the Houston Texans. We can see the dangerous skills he’s employed all over the country.

In December 2020, Jenny Vrentas and Greg Bishop at Sports Illustrated published a damning profile of Jack Easterby, the chaplain and character coach who, by all accounts, is now running the Houston Texans football team. The profile opens with several Texans players calling Easterby the “Littlefinger” of their organization, an allusion to the shadowy operative from Game of Thrones known for secretly pulling the levers of power as people with more impressive titles take the fall for his ill-fated decisions.

The whole article is a fantastic read, but here are the essentials for you right here:

“Conversations with more than 40 people—current and former Texans football operations staff and players, colleagues from Easterby’s time in New England, those from his past in and out of football—provided detailed accounts of his alleged role in, among other things:

Undermining other executives and decision-makers, including the head coach who helped bring him to Houston.

The team’s holding workouts at the head strength coach’s house during the COVID-19 pandemic after the NFL had ordered franchises to shut down all facilities, shortly before a breakout of infections among players.

Advocating for a trade of star receiver DeAndre Hopkins soon after arriving in Houston—one season before Hopkins was sent to Arizona in a widely panned deal.

Fostering a culture of distrust among staff and players to the point that one Texan and two other staffers believed players were being surveilled outside the building.”

According to Vrentas and Bishop, many players and staffers within the Texans organization came forward in the hopes that heightened media scrutiny of Easterby’s antics would open the eyes of Texans owners Cal and Janice McNair, the son and wife, respectively, of the late Bob McNair. It has been four months since Vrentas and Bishop published their profile, and their sources' hopes have fallen flat. Through a combination of quasi-Christian charlatanism and relentless self-promotion, Easterby has won over the McNairs, who show no signs of waking from his spell.

Easterby’s rise to power is a made-for-GoT storyline, but his success also illustrates a more troubling trend in professional sports. When explaining why some teams struggle for years while others find consistent success, front office executives and the sports media alike tend to fall back on the concept of “culture.” The term has become a catch-all phrase for the intangible things that help teams win—or, in the case of a “bad culture,” the things that prevent them from doing so. But the term has become so broad and so ubiquitous that it has collapsed into a sort of tautological self-referentiality: teams that win have good cultures, teams that lose have bad cultures. Beat reporters and blog commentators now spend more and more of their time digging into arcane clubhouse rituals and intra-locker room beef, searching for novel explanations of why a team is or isn’t succeeding on the field.

This singular obsession with “culture” in the abstract obscures a simple, yet apparently forgotten, reality: a team’s performance on the field is a reflection of the decisions—and the checkbooks—of its ownership. Consistently successful teams have owners who are willing to spend money on their franchises and don’t meddle too deeply in the day-to-day management processes. Consistently unsuccessful teams have owners that are cheap, meddling, or both. The latter group occasionally includes owners who do obviously reckless and stupid things like, for instance, forcing stars to play injured in meaningless games, further aggravating their injuries and harming their futures. This equation might not be able to fill a lot of column inches or hours on television, but it is undeniably the best predictor of success.

It is therefore wholly unsurprising that owners like the McNairs latch on to the Gospel of Culture and its chief evangelist, Jack Easterby. From an economic perspective, the relationship between Easterby and the McNairs is straightforwardly parasitic: the McNairs pay Easterby handsomely to spew New-Agey platitudes to their players, and Easterby provides the McNairs with pseudo-spiritual cover for their poor financial decisions. (After two consecutive winning seasons, Houston finished 4-12 in 2020.) From a “cultural” point of view, the relationship is even worse: Easterby shields the McNairs’ imprudence with a patina of spiritual legitimacy, and in exchange, the McNairs allows Easterby to run wild, undermining the work of coaches and mid-level executives while using his supposed monopoly of good vibes to jettison anyone standing in the way of unilateral control of the team. As Vrentas and Bishop put it, “There is a perception inside the Texans’ building that Easterby won a power struggle, completing his climb. And in doing so, these sources say, the character coach brought in to improve the culture has made it worse.”

The dynamic is further exacerbated given that characters like Easterby—or, for the Knicks fans out there, Isiah Thomas—are largely immune from the same professional dangers that befall players, coaches, and even other executives, whose success in their respective roles is at least tangentially related to the team’s performance on the field. By contrast, Easterby, whose only purpose is to soothe the consciences of the owners, is accountable to an audience of two.

If you are a regular viewer of cable news, this charade might sound familiar. There’s no shortage of personalities on talk shows that appear to exist for one purpose—to relay news to the public or provide some expert insight into a topic of common importance—but in reality serve a different function: to provide cover, either directly or indirectly, for the people in power whom they are nominally covering. Bigwigs like CNN anchor Chris Cuomo garnered a platform in the first place thanks to their proximity to authority figures, and then once settled into their position, they shamelessly use it to obfuscate the bad behavior of those who helped get them the job. The younger Cuomo was so successful in this performance that he helped his sex pest, liar of a brother, New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo, win an Emmy. In large part thanks to fawning media coverage, the elder Cuomo took a victory lap last fall in the form of writing a book on his success at containing the pandemic, when he has actually mostly failed to do an adequate job at protecting New Yorkers. Through all of his years in power, Governor Cuomo has developed a workplace that is positively toxic.

This issue is endemic to both government and sports, and it has become significantly worse since the beginning of the Trump era. Bad sports owners, like bad government officials, promote people whose most impressive skill is affirming the decisions of people in charge. Rather than look out for the best interests of their players, those at the top are more attracted to charlatans who make them feel good about themselves. The McNairs might be vaguely aware that Easterby is not making the Texans a better football team, but they don’t care, as long as Easterby knows the right platitudes to whisper in their ears. Leaders build an organization in their own image. People like Jack Easterby and Littlefinger just know how to take advantage of them.

RODNEY’S ROUNDUP

Do you want to read about . . .

. . . boxing and the politics of deprivation? “Puncher’s Chance,” by Declan Ryan in Baffler (March 2021).

. . . Creighton’s Greg McDermott calling the NCAA what it is? “The difference between a plantation and college sports: A plantation didn’t pretend,” by Jerry Brewer in The Washington Post (March 11, 2021).

. . . the latest development in the legal challenge to the NFL’s racist concussion protocol? “N.F.L. Asked to Address Race-Based Evaluations in Concussion Settlement,” by Ken Belson in The New York Times (March 9, 2021).

. . . the incomparable Dave Zirin’s take on these protocols? “So What the Hell is Race Norming?” by Dave Zirin in The Nation (March 12, 2021).

. . . scary backlash against transgender athletes? “The Next Cultural Battle: States Take Aim at Trans Athletes” by Julie Kliegman in Sports Illustrated (March 12, 2021).

. . . tennis style, according to a couple of the greats? “How Naomi Osaka and Serena Williams Reignited Tennis Style” by Rory Satran in The Wall Street Journal (March 13, 2021).