Southpaw 50: Newtonian Logic

Why is the NFLPA protecting Cam Newton's right to endanger himself?

Fear not, dear reader—the two of us survived the biblical flooding in Brooklyn this week, and we even dried out in time to crank out a newsletter (our 50th!).

Before we dive into our topic this week, some shameless self-promotion: Ian has a new piece out in POLITICO Magazine this week on progressive activists’ efforts to oust tough-on-crime judges and “flip the bench” in favor of more reform-minded judges. The piece is built around the story of Robert Saleem Holbrook, a Philadelphia native who spent 27 years in prison before becoming a trailblazing criminal justice reform advocate and a key leader in this latest fight. You can check out the piece here.

In honor of Labor Day, we’re taking a look at two separate unions this week: one that’s trying to protect workers, and one that’s trying to protect itself. Happy reading!

-Calder and Ian

(Cam) Newton’s Laws

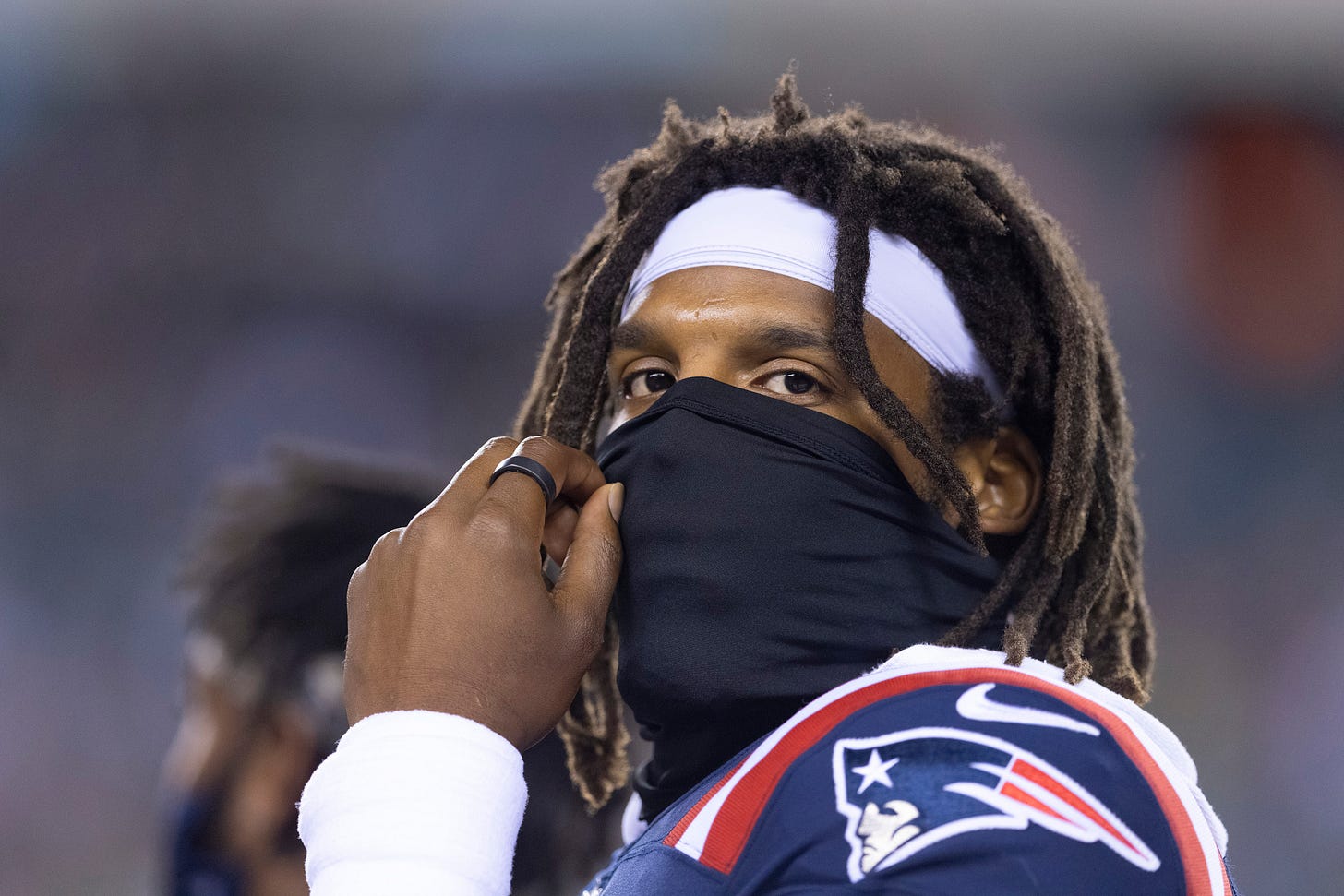

On Wednesday, the New England Patriots released their star quarterback, the former NFL MVP and rookie of the year Cam Newton. Newton’s tenure in New England had been brief and turbulent, punctuated by an untimely COVID diagnosis during Week 4 of last season and defined first and foremost by the fact he turned out not to be Tom Brady. Behind Newton, the Pats finished in third place in the AFC East, posting the team’s first losing record since 2000.

Newton returned to Pats training camp this summer on a one-year, $13.6 million deal, but it immediately became clear that he’d have to duke it out for the starting QB spot with Mac Jones, the Patriots’ first-round draft pick out of the University of Alabama. In the middle of training camp, Newton was forced to miss five consecutive days due to what the team called a “misunderstanding” over COVID testing protocol—a clear indication that Newton had opted not to receive the vaccine, since vaccinated players were not enrolled in the team’s regular testing protocol. On Wednesday, the team released him from his contract and gave the starting job to Jones.

Newton’s release supercharged a debate that’s already engulfed much of the sporting world: should athletes be penalized for refusing to take the vaccine? On Wednesday, Patriots Head Coach Bill Belichick denied that Newton’s vaccination status had anything to do with his release. “No. Look, you guys keep talking about that,” Belichick told reporters. But even from a purely football-centric point of view, there’s good reason to keep talking about it. Five days is a lot of time to miss when you’re locked in a competitive race for a starting QB spot on one of the historically winningest teams in football, and any player would be lying if he told you that missing that many practices didn’t matter. If Newton was on his way to losing the starting job to Jones, carrying a backup quarterback who could contract the disease and cost the team games based on NFL rules doesn’t make much sense.

The more interesting question, though, has to do with politics rather than with gridiron tactics. Earlier in the week, Jacksonville Jaguars Head Coach Urban Meyer had told reporters that the team did take players’ vaccination status into consideration when making roster cuts. Soon after Meyer’s comments, the NFL Players Association announced that it was opening an investigation into the Jaguars’ roster moves, prompting the team to issue a Twitter statement clarifying that no player had been cut solely on the basis of his vaccination status.

The union’s stated purpose is to protect its members, and by that narrow definition, the NFLPA is doing what it’s supposed to, even if some of its members are uninterested in protecting themselves. But judged by the broader goals of the union movement—to protect the interests of the most exploited workers, and thereby advance the interests of all workers—the NFLPA is failing spectacularly.

The NFLPA is operating as if this issue is purely about power when in fact it’s about solidarity. For a contrast, take the 930 members of the Unite Here Local 2, the union that reps concession workers at the San Francisco Giants’ Oracle Park. These workers haven’t gotten a raise in three years, were given paltry help during the pandemic ($500 total), are constantly being berated by drunk, maskless, now sometimes unvaccinated customers—and they aren’t even offered guaranteed health insurance, despite having to work through a dangerous pandemic. According to the union, at least 20 workers have contracted Covid since the stadium reopened, yet their employer has taken no additional steps to protect the workers. Yesterday, 97 percent of the union voted to strike, grinding stadium operations to a halt in the middle of the Giants’ playoff push.

Instead of standing in solidarity with these workers, the NFLPA is busy defending the rights of highly paid players to refuse to take a safe and effective vaccine that would help end the pandemic that’s making them sick. Of course, unions should in most cases be reflexively opposed to granting management more power over their workers—but if there was ever an exception case, this is it.

We are no fans of the people running the NFL here at Southpaw, but in this case, we have to admit: our corporate overlords have gotten it right, and the union is wrong. The league is just trying to protect players, staff, fans, and (most importantly for them) their product—but in this particular instance, they’re also incidentally protecting the long-term interests of workers like those in Unite Here Local 2. The NFLPA is just protecting itself.

And it’s not as though the players’ unions have a tenuous grasp on power to begin with. Due to the strength of the players’ unions, leagues have not been able to impose vaccine mandates on players, so they’ve had to find practical ways to work around them. The NFL, for instance, has ramped up the penalties for missing games, and the NBA has said that it will comply with arena restrictions in places like New York and San Francisco that only allow vaccinated individuals to enter indoor sporting events—essentially forcing players to get the vaccine or else to miss games in those cities.

Of course, we're not that eager to celebrate the leaders of sports franchises just yet. “Sticking it to unions and the people that work for us” is one of the abiding symptoms of ownership. But when it’s not, and when the leagues’ actions align with the interest of sports’ most exploited workers better than the actions of the players unions, we should get behind them. So, we’re ready to applaud (some) sports leagues for doing a little bit to try to keep players on the field and keep their product selling. We’re not ready to cheer about too much else.

RODNEY’S ROUNDUP

Do you want to read about. . .

. . . owners’ sleight-of-hand maneuvering on domestic violence policies? “League Anti-Violence Policies Are Just A Smokescreen For Owners,” by Diana Moskovitz in Defector (August 29, 2021).

. . . the unexpected success of the NCAA’s new NIL rules? “Those NCAA doomsday scenarios about NIL? Instead, it’s proven to be a cleanser,” by Sally Jenkins in The Washington Post (September 3, 2021).

. . . high school sports and climate change?” Louisiana High School Sports Meet a Mighty Opponent: Climate Change,” by Jere Longman in The New York Times (September 3, 2021).