The MLB Lockout is Simple

The headlines about baseball's labor fight make it seem complicated, but the data shows that it's not.

Dear readers,

It’s been a rocky week in the world of baseball. Early in the week, news broke that Calder’s beloved New York Mets had agreed to an eye-popping three-year, $130 million contract with Max Scherzer, the former ace of Ian’s beloved Washington Nationals. Now, Scherzer had already left the Nationals late last season for a brief stopover with the Los Angeles Dodgers—a team that we jointly hate—but Mad Max’s decision to pitch for one of the Nationals’ key division rivals remains a bitter pill for Ian to swallow.

Luckily for Ian, none of this will matter if Major League Baseball and the MLB players union can’t come to an agreement over the league’s collective bargaining agreement, which officially expired this week. That conflict—and what it reveals about the balance of power between management and labor within the league—is the subject of our piece this week. We’ll do our best to make sure that we write about things other than the MLB lockout in the coming months, but we make no promises. This is basically our Super Bowl.

-Calder & Ian

The MLB lockout isn’t as complicated as it seems.

At 12:01 AM on December 2nd, Major League Baseball locked its players out. The lockout—an aggressive anti-labor strategy sometimes employed by management when they cannot come to a Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) with a union—was necessary, according to MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred, because the proposals put forth by the MLB Players Association’s (MLBPA) are untenable.

In a letter released on Thursday, Manfred framed the lockout as a defensive tactic designed to protect the very heart of baseball:

“This defensive lockout was necessary because the Players Association’s vision for Major League Baseball would threaten the ability of most teams to be competitive… We worked hard to find a compromise while making the system even better for players, by addressing concerns raised by the Players Association… When negotiations lacked momentum, we tried to create some by offering to accept the universal Designated Hitter, to create a new draft system using a lottery similar to other leagues, and to increase the Competitive Balance Tax threshold that affects only a small number of teams.”

Now, we don’t blame you if the particulars of that statement make very little sense to you. The negotiations themselves are fairly confusing, even more so for people who haven’t been paying close attention to the ways that owners have manipulated loopholes in the current CBA to keep money in their pockets.

We could give you a full breakdown of the nitty-gritty details of the negotiations (and already partially have). But we’d rather zoom out and look at the bigger picture. Like a lot of coverage of America’s other weird and anachronistic institutions—the Supreme Court comes to mind—the sports media’s coverage of the CBA negotiations can get bogged down in the purposefully confusing and legalistic details of various rule changes and contractual obligations. But if you don’t get too distracted by the finer points of salary floors and service time manipulation, the underlying dynamic is pretty simple: the league wants to make as much money as possible, which means they want to ensure that as much revenue as possible lands in the league’s pockets rather than in the players’. The rest of the backroom maneuvering is just window dressing.

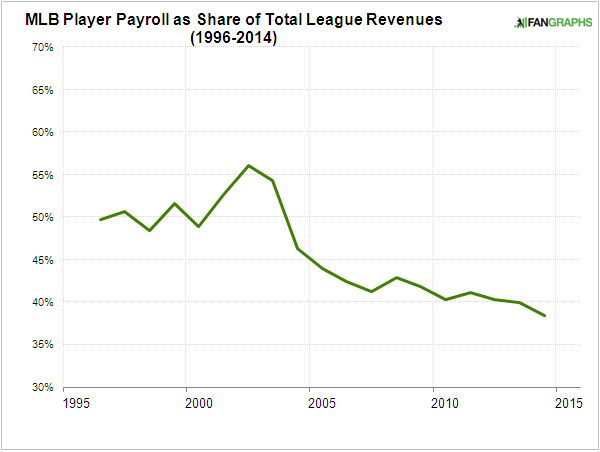

First, it’s fairly clear that no matter what MLB says, its revenue is rising much more quickly than players’ salaries are. The biggest contracts in baseball are getting much bigger—see Scherzer’s aforementioned deal and Corey Seager’s new $325 million deal with the Texas Rangers—but a lot of teams’ overall payrolls are either shrinking or staying the same, with many teams actively trying to tank their way back into relevance with the help of some (barely) reformed McKinsey consultants. Basically, this means that more of the league’s total revenue is going into the owners’ pockets and less into the players’. The good people over at Fangraphs tried to measure this a few years ago, and here’s what they found:

As more teams try not to win, or try to win on comically low payrolls, this trend has only gotten worse. Even many of the richer owners are uninterested in going over baseball’s luxury tax, which basically serves as a soft cap on player salaries. So while they sign lucrative new TV deals and raise ticket, jersey, and concession prices, the money stays in owners’ pockets.

Second, the owners enjoy a dramatic economic advantage over the players. As we’ve written about before, a bombshell report from ProPublica this July showed that sports owners are able to take advantage of a loophole in federal tax law to write the cost of acquiring their teams off their taxes. Using some financial wizardry, which is explained well in the link above, owners are able to report losses on their taxes even if their teams are making money. If their teams are losing money, they can report even more losses. This means that billionaire and millionaire owners incur a tiny tax burden, and it basically ensures that they will profit from their ownership of a team in the short term regardless of whether or not it turns a profit. It makes owners less motivated to succeed on the field, which is the easiest way to guarantee revenue. In short, it creates a glaring asymmetry between owners and players: players actually have to perform well on the field to make money, while owners can just sit back and reap the benefits of their tax breaks.

Third—and most fundamentally—players are the real source of the league’s value. If you’re looking for a particularly dramatic illustration of this fact, just click on over to MLB.com, which, in order to comply with federal labor law during the lockout, isn’t allowed to feature players’ names, images, or likenesses until a new CBA goes into effect. As a consequence, the site has become a content wasteland, featuring boilerplate stories about random episodes from baseball’s past interspersed with stock photos of baseball diamonds and ads for MLB holiday swag. The irony of the situation was not lost on many of the league’s labor-minded players, who trolled MLB online this week by changing their social media avatars to the grey, faceless cartoons that are being used on on teams’ roster pages in lieu of real photos:

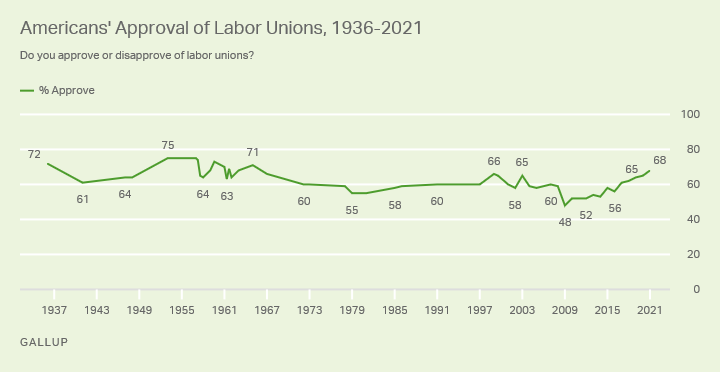

But here’s some good news. After years of declining support for organized labor, there are some subtle signs that public opinion might be on the players’ slide. As the below graph from Gallup shows, support for unions is higher today than it’s been since the 1960s:

The MLBPA is a bit of a unicorn, because it’s a union that represents a lot of rich and famous people, but it certainly seems like more and more people are waking up to the fact that the owners are profiting at the expense of the players—i.e. the workers who actually generate revenue for the league in the first place. That dynamic is certainly at work in baseball’s minor leagues, where a handful of advocacy groups have recently managed to win long-sought-after concessions from the league.

Think about the two graphs in this piece side by side. They are almost mirror images of each other. Major League Baseball players’ share of revenue has gone down while broad-based support for unions has gone up. It’s hard to know at such an early stage how the lockout will end, but if owners think they’ll be able to push around players like they have in the past, the data tells a different story.

RODNEY’S ROUNDUP

“The Origins of Herschel Walker’s Complicated Views on Race,” by Michael Kruse in POLITICO Magazine (December 3, 2021).

“When it comes to China, sports and entertainment often tread lightly,” by Glynn A. Hill and Steven Zeitchik in The Washington Post (December 3, 2021)

“Socialize College Sports,” by Jonathan Chait in New York Magazine (December 1, 2021).

“Sonia Sotomayor may not have ‘saved baseball’ in 1995, but she set it on a path to labor peace,” by Scott Allen in The Washington Post (December 2, 2021).